The ability of humans to learn quickly from small amounts of data shows that today's Deep Learning is likely to be sidelined as new paradigms for neural networks emerge and take over. This is a huge opportunity for researchers. The emphasis on logic inspired AI will likewise be sidelined by approaches based upon plausible reasoning with imperfect knowledge, using ideas refined by a long line of philosophers including Carneades, Locke, Bentham, Wigmore, Keynes, Wittgenstein, Pollock and many others. Symbolic AI was seduced by the purity of mathematical logic, thanks to the influence of Russell, Whitehead and Quine. It is now time for fresh thinking that celebrates the rich ambiguities and uncertainties of everyday life. AI will never be the same again!

Human argumentation is only weakly inspired by logic, and Philip Johnson-Laird has shown that our thinking is based upon considering examples and analogies rather than logic and probability theory. This is an open door for researchers looking to mimic human reasoning, explanations and argumentation, and complements work on statistical approaches.

Common sense is needed to support natural language interaction and everyday reasoning. According to Jim Taylor, it can be defined as sound judgment derived from experience rather than study. In other words, it relies on general knowledge rather than specialised knowledge.

Humans are not a gold standard, as many people exhibit poor judgement, e.g. purchasing things they can't afford, smoking and eating junk food, holding irrational beliefs contrary to the evidence, as well as blatant prejudices against people from different backgrounds. Machine common sense needs to be assessed from a practical perspective, including adherence to ethical principles and standards of normative behaviour. How can we codify such principles and standards? Is it possible to include ethical principles and standards of normative behaviour as part of common sense and to attend to them as part of metacognition, akin to an inner voice?

- Common sense is key to the understanding of meaning in natural language, see: Knowledge-based NLP

Common sense reasoning covers a broad range of everyday knowledge including time, space, physical interactions, theory of mind and so forth. This includes causal models, e.g. things fall if they are not supported, and objects can't fit into containers smaller than themselves. Young children learn a lot of this for themselves through play and through interacting with others.

Children similarly steadily expand their vocabulary, learning words along with their meaning. New words stimulate System 2 reasoning and updates to the lexicon and taxonomic knowledge. Misunderstandings may occur, be noticed and corrected.

We need to gather a collection of utterances and work on a subset of common sense knowledge sufficient for understanding those utterances. It is not a goal to develop comprehensive coverage of common sense knowledge, and the emphasis is rather on demonstrating human-like understanding, reasoning and learning.

Scaling machine common sense will be a matter of learning through being taught lessons in the classroom, including understanding of written texts, and through interaction in simulated virtual environments (playgrounds), with humans and other cognitive agents. In principle, agents can be designed to learn faster than humans, without getting tired and losing concentration. Likewise, agents can be designed to interact with many people as a form of crowd-sourcing whilst preserving their users' privacy. As agents' knowledge matures, they can benefit from recommended reading lists. Once agents have been well trained they will be trivially easy to clone.

It will be helpful to develop visual tools to support browsing, querying and reasoning, including taxonomic knowledge and the graph models constructed in episodic memory.

According to DARPA:

The absence of common sense prevents intelligent systems from understanding their world, behaving reasonably in unforeseen situations, communicating naturally with people, and learning from new experiences. Its absence is considered the most significant barrier between the narrowly focused AI applications of today and the more general, human-like AI systems hoped for in the future. Common sense reasoning’s obscure but pervasive nature makes it difficult to articulate and encode.

The exploration of machine common sense is not a new field. Since the early days of AI, researchers have pursued a variety of efforts to develop logic-based approaches to common sense knowledge and reasoning, as well as means of extracting and collecting common sense knowledge from the Web. While these efforts have produced useful results, their brittleness and lack of semantic understanding have prevented the creation of a widely applicable common sense capability.

Current approaches include:

- Knowledge-based involving informal, mathematical or logic based approaches

- Web-mining based upon identifying assertions or self-supervised learning of large language models

- Crowd sourcing relying on large numbers of non-experts to provide simple assertions

Knowledge-based approaches are hand crafted and far from comprehensive. There has been success in isolated areas amenable to logical theories, e.g. taxonomies, planning and temporal reasoning. The lack of a complete solution may not be a problem for specific applications.

Web-mining and crowd sourcing suffer from a lack of consistency and deeper knowledge. Large language models generate fluent text, but are incapable of deeper reasoning, and invent plausible responses in the absence of real understanding.

Human reasoning operates from imperfect knowledge and what's plausible given past experience. This uses a patch work of informal knowledge rather than mathematically sound principles. It needs to be good enough to understand situations, to make informed guesses as to what will happen next, and to decide on what actions are needed to realise desired outcomes. It also needs to know how to revise existing knowledge as new knowledge is learned.

The quest for comprehensive broad coverage of common sense is perhaps misguided, and we should instead focus on how humans acquire and refine their knowledge, especially in the early years of their lives.

“It is not what you know, but your ability to learn that really matters”

Antoine Bosselut claims:

- Commonsense knowledge is immeasurably vast, making it impossible to manually enumerate

- Commonsense knowledge is often implicit, and often can’t be directly extracted from text

- Commonsense knowledge resources are quite sparse, making them difficult to extend by only learning from examples

Yet according to Ernest Davis, children acquire a good grasp of common sense by the time they are seven. It therefore makes sense to try to mimic human knowledge and reasoning. We need to move beyond lexical models of knowledge and to consider how children generalise from individual examples, and apply this knowledge to make sense of what they read.

Susie Loraine claims that typical six year olds have a 2,600 word expressive vocabulary (words they say), and a receptive vocabulary (words they understand) of 20,000–24,000 words.

Given a six year old has lived for just over 2000 days, this implies vocabulary growth of ten or more words a day. Assuming 10 to 100 common sense facts per word, that amounts to 200,000 to 2,000,000 facts about the world. This compares to ConceptNet with 1.6 million facts interrelating 300,000 nodes. This is a simplification as common sense involves reasoning as well as facts, and this allows children to generalise from specific examples.

“He who learns but does not think, is lost! He who thinks but does not learn is in great danger”, Confucius

Sound judgement is much more than the blind application of learned rules. In other words, you need to think about how to apply what you have learned, and likewise to realise that there is always more to learn as you will never know everything, so you need to keep an open mind and actively seek out new knowledge.

How can we partition common sense knowledge into areas with strong internal dependencies, and weak external dependencies? Can we sort such areas into a dependency graph that gives us an ordering of what needs to be learned before proceeding to other areas? Examples of such areas include social, physical and temporal reasoning.

Benchmarks are one way to assess performance, e.g. scoring agents on their answers to multiple-choice questions, but this fails to explain how an agent understands and reasons. That requires a conversational interface that allows understanding to be probed through questions.

Commonsense reasoning needs to be able answer such questions as:

- What is the meaning of this utterance?

- Why did the person say this utterance?

- What is happening, and why?

- What is likely to happen next?

- How can I achieve my desired outcome?

- How can I avoid or minimise undesired outcomes?

- What are good ways to solve this problem?

Plausible reasoning can be used to identify likely outcomes using causal knowledge and informed guesses. It can also be applied in reverse to identify the most likely causes for a given situation. The kind of reasoning varies, e.g. reasoning about people's motivation vs qualitative reasoning about physical systems. Knowledge can be compiled into rules of thumb for easy application (System 1), but need to be related to explanations in terms of deeper knowledge (System 2).

Plausible reasoning generally involves terms such as likely, unlikely, less likely, and more likely to describe premises and conclusions. This can be contrasted with reasoning based upon Bayesian statistics which involve estimates of various kinds of probabilities, which more often than not are unavailable. Plausible reasoning is limited to a few steps of inference as otherwise the results lack credibility. Further background is available in the page on reasoning.

Folk psychology and naïve psychology are largely interchangeable terms. The former refers to common sense psychology, whilst the latter focuses on child development. Theory of mind highlights that children's social understanding is based on their understanding other people's minds.

These theories refer to mental models used by children for themselves and for thinking about other people, including concepts such as:

- beliefs

- desires

- fantasies vs realities

- intentions

- deceptions

- hopes and wishes

- pretending and imaginary vs factual

- action as an event initiated by a sentient entity, e.g. a person

- causal connections between belief, desire, intention and action

How do children develop and improve their mental models? For instance, when you are very young, you might think that everyone who disagrees with you is stupid and uninformed. As you mature, you may seek richer explanations, e.g. for someone's values, beliefs and desires, as these will offer better predictions for how that person will behave. What kinds of knowledge and reasoning are needed to support this?

In some cases people's mental states are explicit in their behaviour, e.g. facial expressions signifying being happy, angry, or upset. In other cases, it needs to be inferred through abductive reasoning based upon causal models, people's observed behaviour, and relevant contextual knowledge.

In principle, mental models can be a mix of taxonomic facts, rules and algorithms. The taxonomy and rules can be revised when they provide conclusions that run counter to the evidence. An agent could have multiple theories and evaluate which ones work better in particular circumstances, as a basis for generating improved theories and discarding bad theories.

Causal models may be inferred as plausible explanations of observed reality.

Our ability to understand everday scenes is based upon visual commonsense. This enables us to recognise a wide variety of different things and their relationships to each other as part of a scene, including taxonomic knowledge and part-whole relationships. We can direct attention to what is important in the current context. We expand our visual commonsense knowledge by learning across many scenes. This includes behavioural and causal knowledge. Work on graph neural networks and related techniques is showing considerable promise, but further work is needed to integrate commonsense knowledge and reasoning. In principle, this would also enable cognitive agents to learn to solve visual puzzles as found in IQ tests.

Commonsense can often be expressed in natural language, e.g.

- things fall down unless supported by something else

- I am younger than my mother and father

- my head is part of my body

- a dog is a kind of mammal

- a thing can't fit into a container smaller than itself

- fragile things often break when they fall and hit the ground

- flowers are parts of plants, and their colour and shape depends on the plant

- pushing something will cause it to move unless it is fixed in place

- say greetings, introductions and goodbyes when meeting people

- politely offer and receive compliments

- wait for others to finish speaking before starting to talk

- follow directions when you're asked to

- ask for help when you need it

- apologize when necessary

These often involve constrained variables, e.g. "I" is a person, and describe static or causal relationships, involving additional knowledge. In many cases, common sense facts and rules can be modelled as chunk graphs, and interpreted using graph algorithms. This raises the challenge for how common sense is used in natural language processing and everyday reasoning, along with how it is learned and indexed.

The examples suggest the potential for conventions for chunk graphs for expressing rules, but also for the need to justify such rules in terms of deeper knowledge. Human-like agents should be able to explain themselves!

p.s. with thanks to Lexi Walters Wright for examples of social rules.

Many researchers express common sense in terms of a small number of groups of relationships, e.g. Ilievski et al. categorise relations into some 13 dimensions. The following is illustrative and not intended to be complete:

- similarity, e.g. similar-to, same-as

- distinctness, e.g. opposite-of, distinct-from

- taxonomic, e.g. is-a, kind-of, manner-of, disjoint-from

- part-whole, e.g. part-of

- properties, e.g. colour, size, weight, texture, made-of

- cardinality, e.g. most mammals have 4 legs

- spatial, e.g. at-location, near-to, above, below, distance, area, volume

- temporal, e.g. interval, point-in-time, past, now, future, day, night

- ranges, e.g. small, medium, large, very small, slightly small

- comparative, e.g. smaller, larger, quieter, louder, softer, harder

- causal, predicting direct consequences of some event/action

- pre- and post-conditions for actions

- facilitate, e.g. things that help or hinder some action

The set of relationships is open-ended and domain dependent, relying on graph algorithms for their interpretation. The meaning of terms is grounded in the interaction of communicating agents, e.g. if I bring some red balloons to your birthday party, I can be confident that you will agree that they are red rather than some other colour.

One way to probe understanding is to ask a question about a statement, e.g.

S: Jane gave Bob a present

Q: who has a present

A: Bob

S: Wendy gave me a yellow balloon

Q: what is the colour of the balloon

A: yellow

S: the trophy won’t fit into the box

Q: why won’t it fit

A: it is too large

S: John is Janet's dad

Q: is John older than Janet

A: yes

S: Mike is taller than Peter and Peter is taller than Sam

Q: is Sam shorter than Mike

A: yes

S: people can walk into houses

Q: are houses bigger than people

A: yes

Given a collection of such examples, we can develop and test a lexicon, taxonomy and common sense rules for understanding, reasoning and responding. Additional work would allow agents to explain their reasoning, and to learn from experience.

Further examples could be used to demonstrate abductive reasoning in which an agent creates the most plausible explanation for some observations. This involves a chain of causal reasoning about alternative explanations, e.g.

S: Susan picked up her car key

Q: why did she do that

A: she is going to drive her car

S: Marcy reminded Bill to buy some milk on his way home

Q: why

A: they were out of milk

Whilst conventional research focuses on using benchmarks to evaluate new work relative to previous work, that is not the case here, as we are more interested in qualitative rather than quantitive measures. In other words, to show how cognitive agents can mimic human reasoning and learning.

Here are a few resources for further reading:

-

DARPA Machine Common Sense (MCS) Program which seeks to address the challenge of machine common sense by pursuing two broad strategies. Both envision machine common sense as a computational service, or as machine commonsense services. The first strategy aims to create a service that learns from experience, like a child, to construct computational models that mimic the core domains of child cognition for objects (intuitive physics), agents (intentional actors), and places (spatial navigation). The second strategy seeks to develop a service that learns from reading the Web, like a research librarian, to construct a commonsense knowledge repository capable of answering natural language and image-based questions about commonsense phenomena.

-

Commonsense Reasoning and Commonsense Knowledge in Artificial Intelligence, an ACM review article from 2015 by Ernest Davis and Gary Marcus

-

ACL 2020 Commonsense Tutorial which provides a survey of work on applying language models such as BERT and GPT-3 to commonsense, noting that language models mostly pick up lexical cues, and that no model actually solves commonsense reasoning to date. Language models lack an understanding of some of the most basic physical properties of the world.

-

WebChild, automatically constructed commonsense knowledgebase extracted by crawling web text collections, using semisupervised learning to classify word senses according to WordNet senses.

-

ATOMIC knowledgebase describing cause and effect of everyday situations. ATOMIC focuses on inferential knowledge organized as typed if-then relations with variables (e.g., "if X pays Y a compliment, then Y will likely return the compliment").

-

WordNet which is a lexicon that includes a limited taxonomy of word senses.

-

COCA, a corpus of contemporary American English including word stems and part of speech tags

-

BNC, a corpus of contemporary British English including word stems and part of speech tags

-

Linguistics in the age of AI by Marjorie McShane and Sergei Nirenburg, Cognitive Science Department at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

-

ConceptNet is a crowd sourced semantic network now hosted on GitHub. ConceptNet5 is multilingual and based on 34 relationships.

-

Event2Mind, a crowdsourced corpus of 25,000 event phrases covering a diverse range of everyday events and situations. The training and test data are given as comma separated values.

-

Dimensions of Commonsense Knowledge, a survey of popular commonsense sources and consolidation into 13 knowledge dimensions and a large combined graph CSKG (a 1GB tab separated value file).

-

Rainbow: a commonsense reasoning benchmark spanning both social and physical common sense. Rainbow brings together 6 existing commonsense reasoning tasks: aNLI, Cosmos QA, HellaSWAG, Physical IQa, Social IQa, and WinoGrande. Modelers are challenged to develop techniques which capture world knowledge that helps solve this broad suite of tasks.

-

NLP Progress repository, including the Winograd Schema Challenge, a dataset for common sense reasoning. It lists questions that require the resolution of anaphora: the system must identify the antecedent of an ambiguous pronoun in a statement. Models are evaluated based on accuracy. Here is an example:

The trophy doesn’t fit in the suitcase because it is too big.

What is too big? Answer 0: the trophy. Answer 1: the suitcase -

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) cover techniques for applying multilayer neural networks to graphs formed from vertices and edges. Applications include generating scene description graphs from images, and vice versa, generating images from scene descriptions. Graphs can also be used to enable recognition of objects that a recognizer has never seen before, e.g. an okapi is an animal that looks a bit like a deer with stripes from a zebra. Related work automatically generate text descriptions from images, or generate images from text descriptions, see e.g. OpenAI's DALL·E and IBM's Text2Scene.

-

Graphic Causal Models which describe how causality works in terms of what causes what, and are used in statistical studies, e.g. to determine whether smoking is more likely to give you lung cancer, or to determine the effectiveness of a given medication for treatment of some disease. This is complicated by confounding bias, selection bias and other effects. Confounding bias is where the treatment and outcome have a common cause that hasn't been controlled for. Selection bias is due to conditioning on a common effect.

-

Bayesian Networks (see also wikipedia article) are graphical models in which vertices represent random variables and edges represent conditional dependencies between such variables. Bayesian networks can be used to model causal relationships. Probabilistic inference in Bayesian networks is possible using approximation algorithms, e.g. the bounded variance algorithm.

-

Qualitative Reasoning models physical systems symbolically rather than using continuous numeric properties, for instance, replacing a numeric quantity by symbols denoting whether the quantity is increasing, decreasing or constant. Such abstraction leads to ambiguity, producing multiple answers in place of a single answer. Changes can be propagated across causal connections. Phase transitions can be modelled in terms of named phases, e.g. solid, liquid and gas. An example is a kettle left to boil on a stove. The temperature of the kettle remains at the boiling point until all of the liquid has boiled away, at which point the temperature rises rapidly, risking damage to the kettle.

-

Naive Psychology: Preschoolers' Understanding of Intention and False Belief and Its Relationship to Mental World, Jianhua Jian (2006), a study of child development.

-

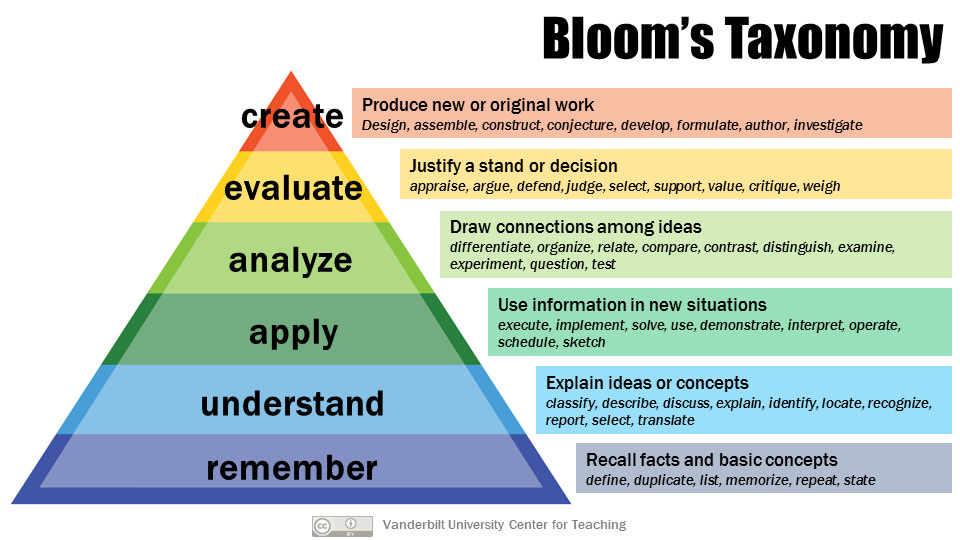

Bloom's taxonomy for educational goals, this has the potential for use in distinguishing different kinds of knowledge and cognitive processes. A revised taxonomy uses the following terms for six cognitive processes: remember, understand, apply, analyse, evaluate and create. The authors further provide a taxonomy of the types of knowledge used in cognition: factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive. See Mary Forrehand's guide to the revised edition.